To do this, the historian should first do patient and meticulous research and then critically analyse the documentation. Furthermore, he should prioritize sources contemporary to the period under study, using later works only as an introduction to the sources. A central topic in Henry Morse Stephens’ thought regarding the writing of history is the question of the truth. In his view, “[the] truth should be the aim of the historian’s quest” (“History”, 1901, p. 52), the ultimate goal of all historiographical work. It should be noted though, that the Scottish historian acknowledged the impossibility of achieving the truth through research: on the one hand, the traces of past that have stood the test of time would never be enough to reconstruct past events in their entirety; on the other hand, the historian, as a human being, would always be subjected to natural limitations that would not allow him to do more than an approximation to the truth. In Stephens’ words, “every historian is unconsciously biased by his education and surroundings and in his historical displays not only his interpretation of the past, but also the point of view of the period in which he lives” (“Nationality and History”, 1916, pp. 225-226). But the historian went further: in his perspective, each generation of historians narrates its own interpretation of the past, and it is this permanent change of interpretation that allows “the perpetual re-writing of the long story of man” (Idem, p. 225). It is curious that, although his reflections reveal the influence of the intellectual and historiographical trends of his time, the Scottish historian has demonstrated a remarkable historical consciousness.

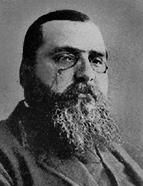

Henry Morse Stephens died on April 16th, 1919, in Berkeley (California), after many years devoted to research and teaching of History.