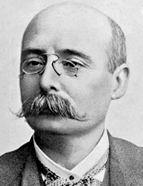

He used the concept of progress in two senses. On the one hand, it meant a belief in the permanent technological, economic and political improvement of societies, with a view to democratisation. On the other hand, it meant the evolutionary process which he believed guided reality. Societies were more civilised the more clearly they had replaced the forms of thought, industrial and cultural production inherited from previous peoples with more advanced forms. In this sense, permanent progress — more or less rapid — governed reality. However, Consiglieri Pedroso argued that there were also anomalous events, similar to biological diseases, which affected the march of progress without ever stopping it. The "social organism" could have acute illnesses: wars, revolutions or coups; or chronic illnesses: prostitution, misery and immorality. There were also fortuitous influences: events that represented the presence of past ideas and traditions, but which did not affect the progress of the consciences of the present time. Consiglieri Pedroso evoked the example of the First and Second French Empires. With the democratisation of Portugal and Europe as his goal, he defended press freedom as the president of the Association of Journalists and Men of Letters: he fought against Bill 27-A in 1907. Since 1875, he had fought to reduce spending on the royal household, the army and embassies, so that free trade could be established when the Portuguese economy was ready to compete with more solid economies. He defended grain protectionism and the improvement of living and working conditions for industrial workers in the Chamber of Deputies. Between 1874 and 1907, he developed a pan-Latin and anti-Germanic vision for perpetual peace in Europe. Following the Franco-Prussian War (1871) and thanks to France's diplomatic isolation, which was broken in 1891, he defended the idea of dividing Europe into racial blocks: Latin, Germanic and Slavic, which would be organised according to the origin of the languages and customs of the constituent nations, which he argued shared common historical developments. He also focussed on improving Portugu ese-Brazilian relations via the Lisbon Geographical Society. After the entente cordiale (1904) and the Anglo-Russian Convention (1907), he argued that the Triple Entente would be able to stop German expansionism and lead to the future formation of blocks (Brasil-Portugal…, 1906, p.99), which would ensure fraternity between nations until the United States of Europe became a reality. He died on 3 September 1910. In his funeral eulogy, Aniceto Gonçalves Viana, a member of the Lisbon Geographical Society who had travelled with the deceased to Russia in 1896, highlighted his knowledge of languages (he spoke eleven) and his personal motto: he who lasts wins .

This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P, in the scope of the projects UIDB/04311/2020 and UIDP/04311/2020.