His work at CODENO and SUDENE—advocating that drought was a consequence of the problems in the Northeast and that the socio-economic structure of the region was responsible for the problems because it was a result of the colonial model—certainly explains his appointment as Minister of Planning in the João Goulart government from 1962. He then drew up the Triennial Economic and Social Development Plan with the aim of controlling inflation and promoting basic reforms for the development of a nationalist and progressive capitalism in Brazil. The basis of his proposals for state action was the method of historical-structural analysis—the endeavour to explain structural underdevelopment on the basis of medium and long-term historical conditions. If the assumption was that the integration between the distributive structure and the supply structure was causing a stagnation, especially considering the technological heterogeneity with economic areas that were extremely advanced and others quite backward, it would be up to the state to draw up policies to induce development. Still in 1963, he returned to SUDENE to promote a policy of tax incentives for investments made in the Northeast, the underdeveloped area of Brazil that due to his personal life story and the result of applying the aforementioned method, had always been the centre of his concerns. The 1964 military coup exiled one of Brazil's most prolific economists in the very first months of the regime of exception. The basic reforms had to be prevented, and Celso Furtado was enrolled in Institutional Act no. 1 in 1964, beginning his years of exile that would last until 1979, when Brazil's Amnesty Law was passed.

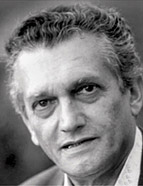

In his autobiography, Celso Furtado called the years between his appointment to ECLAC in 1949 and his work at SUDENE—which lasted until the 1964 Military Coup—an "organised fantasy" and an "undone fantasy." This was a period during which he put together a theory of underdevelopment and a narrative of its historicization. He also put forth a set of public policies that would rescue the Northeast and rescue Brazil from underdevelopment. After these years, between his imposed exile and his return to Brazil, "O Velho" [The Oldman]—as the Brazilian-born Portuguese economist Maria da Conceição Tavares used to call him—brought comfort to his fellow economists who had inherited his disdain of underdevelopment through his constant public intervention, whether in academic circles or through political action in specific positions. In exile, he taught in Santiago de Chile, Yale, and Paris. He was a professor of Economic Development at the Faculty of Law and Economic Sciences of the University of Paris. He was the first foreign professor appointed at a French university. He also taught in Washington, Cambridge, and Columbia. During his time away from the country, when he was only able to return for sporadic seminars, he published Subdesenvolvimento e estagnação na América Latina [Underdevelopment and stagnation in Latin America] (1966), Um projeto para o Brasil [A project for Brazil] (1968), Análise do modelo brasileiro [Analysis of the Brazilian model] (1972), O mito do desenvolvimento econômico [The myth of economic development] (1974), Criatividade e dependência na civilização industrial [Creativity and dependence in industrial civilization] (1978), among other works.

This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P, in the scope of the projects UIDB/04311/2020 and UIDP/04311/2020.