He follows on from this with the striking observation: " It was not the notorious Inquisition that served as the firewall safeguarding the framework and references of the Catholic vision that conditioned Portuguese culture until the 19th century; it was the spontaneous defence of orthodoxy that made the Inquisition possible ” (p. 41). Finally, as another illustration of the theoretical underpinnings shaping Lourenço’s worldview, he concludes the same essay with this assertion: " The profound life of a culture does not move according to the laws that alter the political, economic, or even social status of a society ” (p. 42).

It should also be noted that a significant portion of Eduardo Lourenço’s articles and essays addresses the question of the colonial empire. For example, one might consider the volumes Situação Africana e Consciência Nacional [African Situation and National Consciousness] (1976) and Do Brasil. Fascínio e Miragem [On Brazil: Fascination and Mirage] (2015). Additionally, many of these texts are strongly critical of the empire: slavery, he argues, “was, probably, the greatest sin in our history” ( Ler , p. 32). Another revealing and noteworthy passage can be found in O Fascismo Nunca Existiu [Fascism Never Existed]: " It is true that, modest Cortéses and Pizarros, our empire’s pioneers ended up carving out in the African hinterlands authentic homelands of their own that seemed to extend the kingdom or the republic from which they had departed. It is no less true that, whether kingdom or republic, from time to time, with delayed spasms of recovery, they would endorse this existence, controlling it from afar just enough to extract its fruits ” (p. 99).

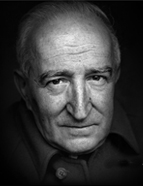

Lourenço’s historical vision is always expressed in an evaluative register, as opposed to an analytical, distant, empirical, and neutral narrative. It is consistently critical, juxtaposing the thinker’s worldview with the historical realities he examines. He never hesitates to make value judg e ments, clearly motivated by a profound passion for Portugal, heightened by the fact that he observed, studied, and experienced it from a distance; that he had to explain it to foreigners; and that he longed for the homeland he always considered his own. In summary, Lourenço offers a complex vision of Portuguese history, resistant to any oversimplification (including this attempt at synthesis). While it remains scattered across a multitude of writings yet to be fully collected in a single volume, it nevertheless reflects one of the most coherent interpretations of Portugal. His approach is animated by what Max Weber defined as Verstehen : an empathetic understanding from within.

This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P, in the scope of the projects UIDB/04311/2020 and UIDP/04311/2020.