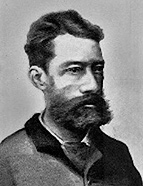

Alberto Sampaio, tracing his profile and analysing his written work, defined “three cycles” in his intellectual career: the first, consisting of poetic compositions, would focus mainly on the year- , 1855; the second, corresponding to his literary and sociological studies, would cover the period between 1856 and 1874; finally, the third phase, undoubtedly the most important, would include his historical and archaeological studies, from the latter date until his death in 1899. With regard to the first aspects, his close friendship with Camilo Castelo Branco is significant, beyond what he wrote, a lesser-known aspect of historians, but often emphasised when analysing his biographical profile and as a man of culture. Sarmento is, in fact, particularly recognised as an archaeologist and readily accepts the title of ‘excavator of Citânia ’. But, naturally, he reacted with irritation to the derogatory term “digger of mounds” used by a minister of the kingdom, the Duke of Ávila and Bolama , to express his displeasure at the fact that the man from Guimarães had refused the Order of St James, after some controversy surrounding this award (Cardozo, Francisco Martins Sarmento...1961, pp. 5-6).

As far as his thinking is concerned, if any topic runs through it, it is his full integration into the deeply nationalist cultural framework that had such an influence on the intellectuals of the second half of the 19th century. With regard to his specific intervention, the ethnic and cultural characterisation of the Lusitanians, whom he considered our ancestors, is particularly noteworthy. In line with his contemporaries, the scholar from Guimarães also believed that the main issue at stake was to define the essence of the “Portuguese man”, in this case through an analysis of his most distant ancestors, especially the populations that preceded the Romans in this territory. In this particular aspect, Sarmento distances himself from the perspective of Alexandre Herculano, who contested and rejected, with good arguments, the establishment of a link between pre-Roman realities and the contemporary world. Despite the validity of this position, characteristic of nineteenth-century positivism, it is clear that many of those who devoted themselves to the study of the pre-Roman past of the Iberian Peninsula, including Leite de Vasconcelos, did not share it. Sarmento’s originality, an aspect he always made a point of emphasising and extending to various fields, lay in his unique interpretation of the geography and, especially, the ethnology of the Lusitanians. With regard to the former, his idea was to attribute to them a territory stretching from central Portugal to the extreme north-west, encompassing the Gallaeci and Lusitanians in the same cultural reality, conveniently interpreting a passage from Strabo. Although his interpretation includes some less common aspects (such as linking the Lusitanian world to the castros of the north-west), it does not conflict with other contemporary or even more recent historiographical perspectives. In any case, what stands out in particular is his conviction that “the civilisational unity of the ancient Galicians and Lusitanians” was not for him “a new problem, but an old dogma” (Sarmento, Dispersos , p. 165). This ancient affinity, in his view, would continue throughout the centuries and could still be verified in his own time.

This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P, in the scope of the projects UIDB/04311/2020 and UIDP/04311/2020.