Curiously, in Clenardo, Cerejeira «comes across as surprisingly Machiavellian and economistic», relying on António Sérgio to explain the non-development of sixteenth century Portugal (Luís Salgado de Matos, «Cardeal Cerejeira... », Análise Social [Social Analysis], 36 (160), 2001, p. 807).

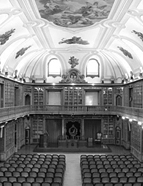

Cerejeira only retained the method of positivism, stressing «albeit its rejection as philosophical» Do positivismo, Cerejeira reteve apenas o método, acentuando, no entanto, «refugado ele porém como filosófico» (A Igreja e o pensamento contemporâneo [The Church and contemporary thinking], 1924, p. 223). As regards the facts, this method was followed by political integralists and history teachers in Coimbra, which made it difficult for them to assume the role of understanding rather than explanation from an early stage, although in 1933 Joaquim de Carvalho had already transmitted a public alert in a speech during an opening ceremony in the Sala dos Capelos [Great Hall], when referring to a friend and colleague, a teacher of Aesthetics and History of Art: «As an art historian, [...] his studies were guided by explanation, and not only understanding. He is a positivist if I may so express. He inventories facts like no one else in our time, and pursues the objective connections between them, and if these facts and these connections do not spring forth with the scent of pure aesthetic sensibility, it is because they aspire to the perennial glory of scientific foundation. I do not know if the scientific approach is possible in art, because the artist does not circulate within the realm of facts, but rather within that of values» («Discursos» [«Speeches»], Biblos, 9, 1933, pp. 501-502).

The method imposed an external and internal criticism of the document in pursuit of rigour and certainty. Both A. de Vasconcelos and Cerejeira and, in fact, all the teachers assumed this approach until the 1930s. This trend, which was also followed by their students, became drier through Neo-positivism, whereby adjectives and moral judgements were prohibited, at least in the mid-1950s, the decade that was marked by the History crisis within the Faculty.

For example, Sílvio de Lima, when referring to Cerejeira, before the confrontation of ideas that victimized him during a period of intolerance and new cleansing, stated that among his colleague's many professional qualities was «the prudent critical attitude that prompted him to check before stating, so aware is he of the human passions that adulterate the facts» (Moreira das Neves, O cardeal Cerejeira [Cardinal Cerejeira], 1948, p. 199).